A bitter historical conflict has raged and continues to rage between India, Burma (now officially Myanmar), and the Naga people since the Naga declaration of independence on August 14, 1947. The British began the forced annexation of the Naga homeland and colonization of the free Nagas, which was continued by India and Myanmar until the entire Naga homeland was arbitrarily divided and colonized by the two countries against any civilized law, and continues even in the twenty-first century, 2022, at the cost of thousands of human lives.

This bitter experience by the Naga people in 2022 turned out to be one of the most significant opportunities to learn more about the harsh realities of regional geopolitics associated with the conflict between India, Myanmar, and the Naga people. It also helps to see and understand international relations from a broader perspective, such as how India and Myanmar continue to effectively collaborate in suppressing the Naga people’s rightful aspirations.

The Naga people, as well as observers of the Naga political issue, should bear in mind that there are three “hard truths” and a “soft truth” are necessary for diagnosing the India-Naga-Myanmar political conflict now and in the future.

The first hard truth is that India and Burma (now officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar) declared independence from colonial British rule on August 15, 1947, and January 4, 1948, respectively. By contrast, the Naga people did not sign (refused) the Panglong Agreement of February 12, 1947, which was instrumental in forming the Union of Burma (Constitution), and went on to declare their independence from colonial British rule on August 14, 1947.

The second hard truth is that India and Myanmar had treated the Naga people as underdeveloped and had maintained “rules of procedure” that allowed them to act arbitrarily in Naga affairs. For example, consider the arbitrary division of the Naga homeland between India and Myanmar. To make matters worse, Naga people working in institutions under the control of India and Myanmar are compelled to comply with India and Myanmar’s arbitrary wishes. They have no choice because if they defy either India’s or Myanmar’s diktats, they will be terminated, transferred, or labeled/framed as anti-state and booked under various laws in either India’s or Myanmar’s courts. Unfortunately, the media has never exposed all these despicable tactics.

The third hard truth is that, while in theory, India and Myanmar are guided by human rights principles in making their decisions, in practice, the interests of both India and Myanmar trump all civilized laws or principles. For example, in the case of India, the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act – AFSPA– a controversial & draconian law enacted in the Indian Parliament for the first time in September 1958 based on a draconian ordinance used by the British colonial rulers during the Quit India Movement of 1942 in the context of the Naga national movement that grants military forces and the air forces operating as land forces, and includes other armed forces of the Union in “disturbed areas” “certain special powers,” including the right to shoot to kill, raid houses, and destroy any property that is “likely” to be used by suspects, and “arrest, without a warrant, any person who has committed a cognizable offense or against whom a reasonable suspicion exists that he has committed or is about to commit a cognizable offense and may use such force as may be necessary to effect the arrest.” Some of the most heinous incidents that occurred under India’s AFSPA include the Matikhrü massacre (Pochury Black Day, 1960), the Oinam case (Operation Bluebird/1987), the Mokokchung Massacre (Ayatai Mokokchung, 1994), and, most recently, the Oting Massacre (2021). While in Myanmar, according to a 2016 report by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) has been conducting a brutal force conversion campaign of Naga people to Buddhism since 1994 by occupying Naga villages, burning down churches, forcing labor, torturing, and forcibly converting at gunpoint.

There is one equally important soft truth that explains why the political conflict between the three entities continues to exist today.

The soft truth is that, while in theory or diplomatic language, India and Myanmar welcome a peaceful resolution to the India-Naga-Myanmar political conflict to bring permanent peace in the region, but in practice, both countries continue to openly employ divisive, military, anti-peace, and anti-conflict resolution strategies in dealing with Nagas’s inalienable rights. One classic example is that India and Myanmar have taken the most hypocritical approach in continuing forced occupation (to retain control and administration) or colonization of Naga homeland. Any attempt or call for third-party intervention in the Indo-Naga-Myanmar political conflict is directly blocked or opposed as a matter of internal affairs by both India and Myanmar, as allowing a third-party intervention would jeopardize their regional strategic dimension and control over the Naga homeland.

While the three entities have been discussing how to resolve the historical conflict separately for decades, several approaches have been adopted and signed/announced in order to create a negotiation platform, the most notable of which was the 1964 Ceasefire Agreement between the Government of India (GoI) and the Naga National Council (NNC), 1997 (GoI and the National Socialist Council of Nagalim – NSCN), 1998 (GoI and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland – NSCN-K), and the 2012 regional bilateral ceasefire agreement between the Union Government of Myanmar represented by Sagaing Region and NSCN-K.

With the signing of the 2015 “historic” Indo-Naga Framework between the GoI and the NSCN, witnessed by India’s Prime Minister Modi after previous resolution attempts such as the Akbar Hydari Agreement (1947) and the Shillong Accord of 1975, progress appears to have been made on the resolution of the Indo-Naga political conflict. However, the signing of the Agreed Position in 2017 between the GoI and the Naga National Political Groups (NNPGs) to resolve the same issue created a Naga conundrum – a conundrum of which is better. While the Myanmar-Naga political conflict had seen some hope for resolution following the signing of the 2012 bilateral agreement, the Tatmadaw’s takeover of the NSCN-K headquarters in Taga under the Naga Self-Administered Zone of Sugaring Region in 2019 can be seen as a dilution towards the possible resolution of the conflict. One key reason is that, while both India and Myanmar want a peaceful resolution in theory, the actions of the GoI/India in signing a separate agreement to resolve the same conflict and the Tatmadaw/Myanmar overrunning the NSCN-K HQ despite the bilateral ceasefire agreement demonstrate how India and Myanmar are questionable and how both adamantly opposed to a peaceful resolution to the historical conflict.

Therefore, only when India and Myanmar accept ‘resolving the historical and colonial conflict,’ an international conflict that transcends national boundaries is in the interest of humanity and their long-term national interests, they will give a chance to a win-win negotiated settlement over zero-sum approach. Despite, misunderstandings and the fight for legitimacy within the various Naga organizations, the Naga people should not give up hope on the win-win resolution approach for collective good and humanity. No one knows when a win-win resolution or even a trilateral discussion between the three entities will occur; however, those sitting at the negotiation table should take into account the four critical truths outlined above. The hard facts will not change; however, with smart strategies, the soft truth can be altered.

Author’s Disclosure Statement: Augustine R. is an independent researcher on the India-Naga-Myanmar political issue, as well as on broader global security and strategic issues. He is also the Editor-in-Chief and Publisher of the International Council of Naga Affairs (ICNA) web publication platform and does not work for, consult for, own shares in, or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article/opinion.

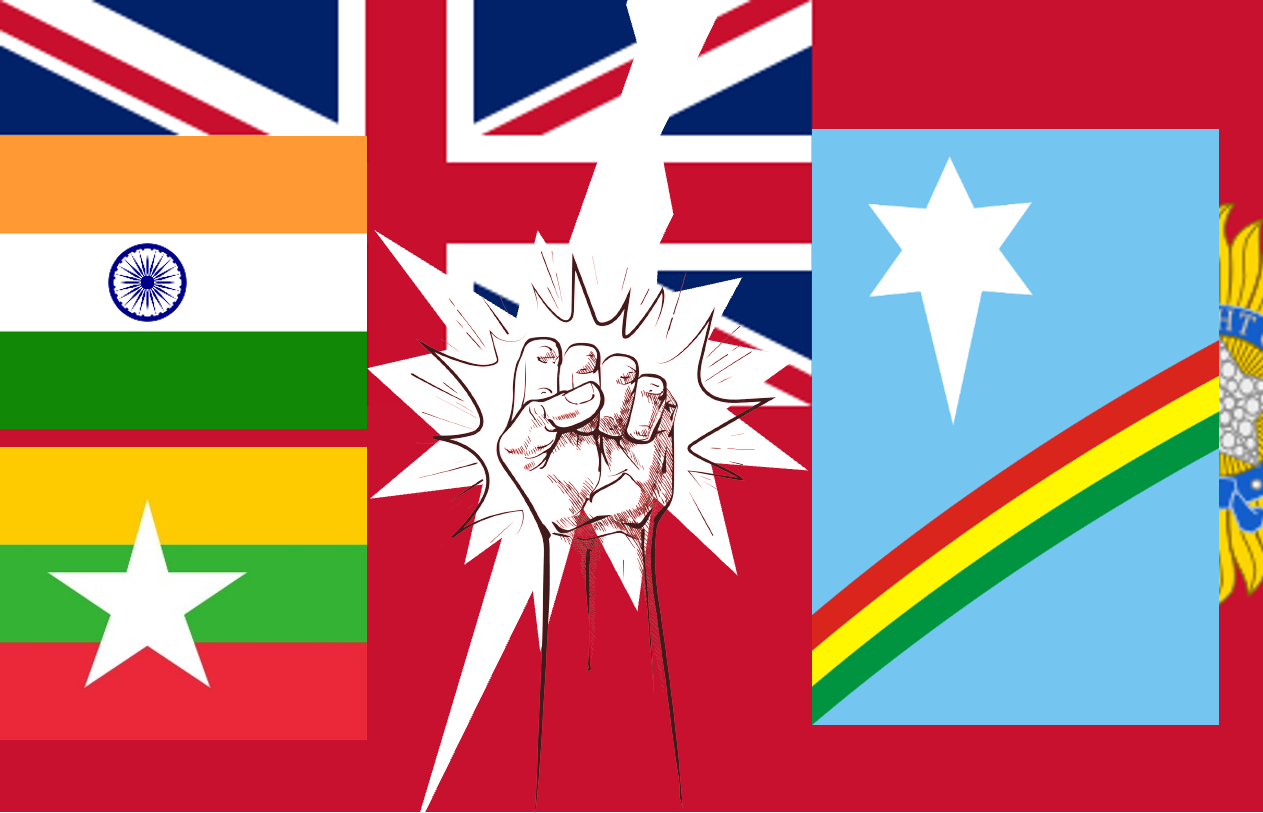

Featured Image: Flags of British India, India, Myanmar, and the Naga National Flag / Reworked by International Council of Naga Affairs (ICNA)

ICNA reserves all rights to the content submitted. The author’s views are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of nagaaffairs.org